The landscape of emotion

Written by John MacphersonWhat I love about this blogging lark is the way that connections get made. And my recent posts on ‘landscape and meaning’ led photographer Henry Iddon to comment, but also provide a link to an ongoing project he’s labouring away with: ‘A Place to Go’. As Henry describes it:

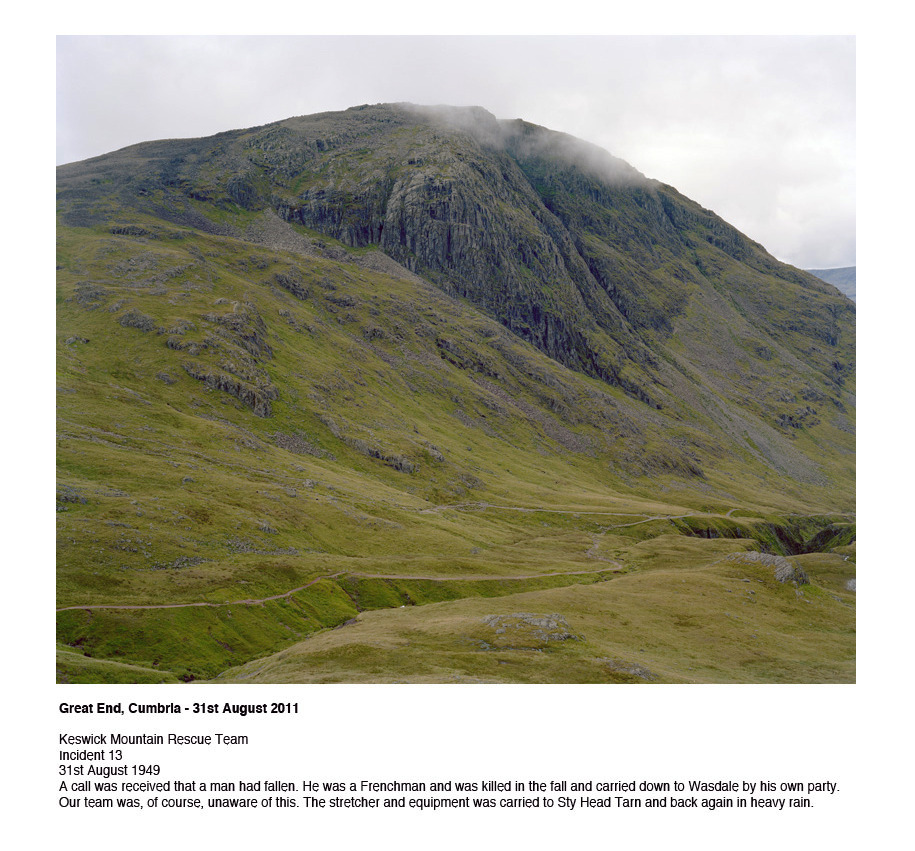

A Place to Go – sites of mountain misadventure.

A work in progress, shot on 5×4 large format, that aims to consider the mountain and wilderness landscape, and how the infinite power and scale of the natural environment dwarfs humanity.

What this work hopes to do is go beyond the barrier, that picture postcard one dimensionality that is often found when looking at a mountain landscape. To make images, with supporting text, that imbue a place with emotion. Mountain landscapes will not always be simple ‘places of delight’ – scenery as sedative, topography so arranged to feast the eye.

What we see with our eyes is influenced by what we know, however much that contradicts the way we have been taught to view the upland landscape as a place of benign beauty.

I was intrigued by this work for a couple of reasons, firstly it directly related to the subject matter I was exploring in my recent posts, the hidden layers of meaning in ‘landscape’; and as someone born in the mountains, and who has walked, run, climbed, cycled and skiied on them, and simply contemplated them, they are ‘places’ I am very familiar with, and intrigued by.

Anyone who has spent time in and around mountains knows both their beauty and their danger. One often the precursor to the other, the unwary lured ever further only to be caught unawares by a sudden storm, a slip, trip or fall. And unlike road accidents where the family of the bereaved are able to visit the spot of the mishap and often leave a small note, a bunch of flowers, or sometimes even a small memorial marker, the very terrain of the mountains that contributed to the incident makes a visit by grieving relatives unlikely in the majority of cases. And so it is generally the case that no physical on-the-spot record, or evidence, exists.

An ‘incident’ in the mountains generally elicits an MRT response (Mountain Rescue Team), comprising volunteer men and women from the local community whose mountain skills and local knowledge are vital. However the cold statistical record keeping of the MRT log betrays very little: ‘A man has fallen, he was French, he was killed….etc’. But this belies the very real ‘connection’ that rescuers feel with this landscape, and with the potential ‘casualty’.

There is a transformative element to a search/rescue: the landscape that you see portrayed above in Iddon’s photo, as an example, may not mean much to a casual viewer, save its ‘epic’ nature: we wonder at the scale and ‘wildness’ of its terrain. But seen through the prism of experience of a rescuer, other details become crucial.

I have always been struck when in the mountains by the remarkable similarity between a fingerprint and the whirling looping contour lines of a map. And just as each of us are unique, so too is the landscape, no duplication ever of the folds and cuts in the land, the bunching contours that reveal the presence of steep crags and gullies. For the MRT members, these contour lines are the story of the landscape they must read to try to predict what might have occurred:

“If the missing person followed this line from the path by mistake they may have slid into this gully in the failing light…..we should look there…”

“If they walked on the lee slope the snow deposition may have slowed them and they may be lower down the hill than we thought….perhaps some of the team can look down the slope for a spell…”

“The navigation in this area is complex, short navigation legs are safer, maybe they took a single bearing and fell into the big gully…lets come in from below and search the foot of the crags….”

The safety of the MRT members also depends on reading this story of the land accurately too. Where can a helicopter land safely? Will the team be at risk from avalanche in this area?

But all of this ‘reading of land’ is only one aspect of the relationship with ‘place’ that occurs in such situations. There is a strong emotional connection too.

Many of my close friends are in the Lochaber Mountain Rescue Team, probably one of the busiest MRT’s in the UK. I have seen the personal involvement these men and women develop with the missing person/casualty. Missing persons are the worst, at least with a casualty in a particular location you can concentrate physically on doing what’s required to retrieve them. But a missing person is altogether different, and I can recall several incidents of missing persons where long after the ‘call out’ became a ‘search’ rather than a ‘rescue’ and then was scaled down as it was unlikely the person was still alive given the weather, and the period of time that had passed, several of the team continued in their own time over a period of months looking, thinking, wondering, and looking again for the missing person.

And with this emotional ‘connection’, folds of land and hidden corners ‘off the beaten track’ that go unnoticed, become places of potential concealment and enquiry, then committed to memory as having been searched, and sadly found to be ’empty’. And always present is a ‘line’ connecting the missing, the searcher, and those who grieve over the absence of a loved one; these are the ‘contours of loss’, the highs and lows of emotion that will never be revealed on any map.

MRT members volunteer for this very humane interaction with the mountain landscape because they love the hills, and are happy to share their skills to assist fellow mountaineers and walkers needing help, because one day that could be any one of us.

And there’s the irony in all of this that the vast majority of experiences in these places are uneventful, people climb and walk, enjoy their day and it all goes unrecorded unless a blogger or diarist makes a note about the outing. And so we have this curious situation of the small minority of mountain users who become casualties and a ‘statistic’ but whose misfortune triggers a written recording of the tragic events of their day:

Lake District Mountain Rescue Association Annual Report 2007

Incident 422 17215 30 December 13:13 Sharp Edge, Blencathra NY327284

Dry with cloud cover. Wet and slippery Rock Scrambling (Not known)

Man (60) – Subject slipped and fell approximately 100ft down gully to north side of the “Awkward Step”

Alarm raised by other walkers who went to his aid, including administering CPR. FATAL Multiple and serious injuries

Keswick 25, 41/2 hr, Penrith 5, 3hr; Boulmer SAR Helicopter

Henry Iddon’s detailed and contemplative photographs transform these objective records of a mishap and enable us to make an emotional, human connection with ‘place’. His images pay his respects to these high, wild and alluring places, but they also pay tribute to those individuals whose life stories ended upon their wild slopes.

For those of us who end our days in ‘ordinary’ ways, there will be erected a stone, hewn by man, and inscribed with words as memorial to our presence and passing. For those whose life ends on a mountain, what greater memorial can there be than that cold stone, hewn by nature, written upon by the passage of time and weather, and towering over all of us.

These are truly sublime photographs, and are ‘epic’ landscapes in the proper sense of the word, and that’s the highest compliment I can pay them.

(“Epic: A long poem, typically derived from oral tradition, narrating the deeds and adventures of heroic or legendary figures or the history of…”)

Discussion (12 Comments)

Etheral landscapes that echo heaven seem very appropriate given the subject matter. I wonder if equivalent images in an urban environment would echo a more hellish end?

Thanks for commenting Patrick. I’m not sure. There are many quiet corners in urban environments surrounded by high buildings, hustle and bustle, where I’ve come across little plaques or tree carvings where ashes have been scattered, the place obviously ‘symbolic’ to the deceased or their successor.

Personally I’m not that concerned with the ‘majestic’ nature of the place so much as the personal sense of connection that an individual has with it. And that connection could be with an urban park in which they watched nature’s cycle over their lifetime, or saw their children grow or whatever.

There’s as much ‘wildness’ in the small stuff in our back gardens as on lofty peaks, its really how close we want to get to it in order to be able to appreciate and contemplate it.

I don’t subscribe to the notion that death in an urban situation must of necessity be ‘hellish’ as an opposite of death in high places being sublime.

The landscape cares not, only us.

Thanks John and RadiantFlux.

‘Edgelands’ by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts ISBN 9780 2240 89029 looks at ‘England’s true wilderness’ – the marginal wastes in and around urban areas. It’s a sort of MacFarlane ‘Wild Places’ for conurbations.

Thanks Henry, will add that to the reading list. I can recommend Kathleen Jamie’s writing on the human connection with (urban) landscapes in ‘Findings’. Well worth a read if you’ve not already done so.

Will have to check that out – rather a long list at the moment! Looking forward to Nan Shepherd – The Living Mountain

I know I know sorry! Same here too many books not enough time…….!

We never nkow when we are going to leave this planet. Generally we do not go to the hills thinking we will not return. This book looks great – addresses many difficult questions but asks some too…

Nice work, Henry. I’ll check that out!

Hi Jerry – I think it would be splendid to see in the flesh, large prints filling your field of view.

Nice piece about H’s project. I did something on H’s Spots of Time called Moonlight & Natural Magic. It’s on my website under Recent Writings and on UkClimbing site. Speaking of climbing doing a workshop in Pyrenees in June with John and Anne Arran.

Thanks Paul, appreciate the feedback. Will certainly have a look at your piece in the next few days. Thanks for highlighting it.

Nice piece on H’s project which I have loved seeing him develop over the last year or so.

I did something about H’s Spots of Time project which may be archived on UkClimbing site. It’s on my Recent Writings page http://www.hillonphotography.co.uk and called Moonlight & Natural Magic

‘