Colonialism and visual culture

Written by John Macpherson

‘Kongouro from New Holland’ by George Stubb

I almost fell off my chair yesterday when I heard that statement, particularly the comment in that last paragraph “…represent the beginning of Australia’s rich visual culture…”.

The same comment was reported in several news items this week, but to my utter astonishment went unchallenged by any correspondent. I thought it might be a misrepresentation of something said and then not correctly reported by the press. But to my surprise it was accurate, repeated verbatim in several papers, the quote accurate, and originally appearing in reports from the Australian media.

This one comment, from a (presumably) well-informed professional in the Australian art world, at a stroke and with breathtaking arrogance, completely dismisses the rich aboriginal visual culture that predates European colonization by tens of thousands of years.

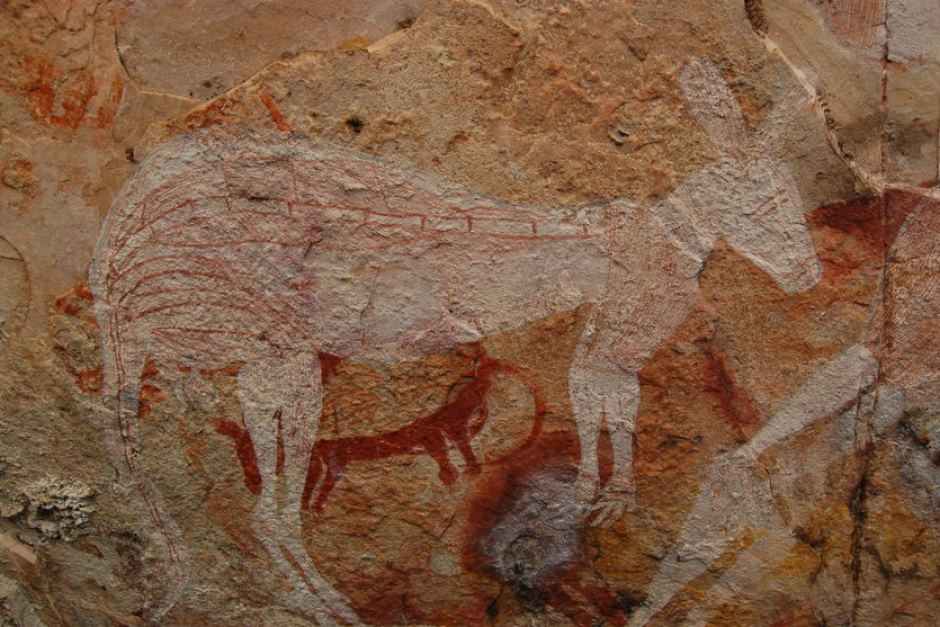

Aboriginal rock art kangaroo. image © abc.net.au

Truth is, aboriginal rock art is one of the oldest continuous art traditions in the world. Many Australian rock art sites have been carefully examined and determined to be about 40,000 years old, and some are even older. The art is not simply decorative, but contains stories and symbols based on ‘the Dreamtime’, the stories handed down from generation to generation for tens of thousands of years, and which are celebrated in songs and ceremonies that continue to this day.

It is perhaps not insignificant that aboriginal representations of ‘kongouros’ invariably show them facing forwards, yet the very first European painting of one of these animals by Stubb has the animal looking over its shoulder, wary, ready to flee. Art at its most revealing, hinting strongly at the ways differing cultures interpret and interact with the world around them, and are thus reflected in the artwork they create.

Aboriginal art is still widely practised, is highly collectible, and continues to reflect the rich visual culture of Australia. But there’s aboriginal photography too. One photographer in particular stands out for me, Michael Riley.

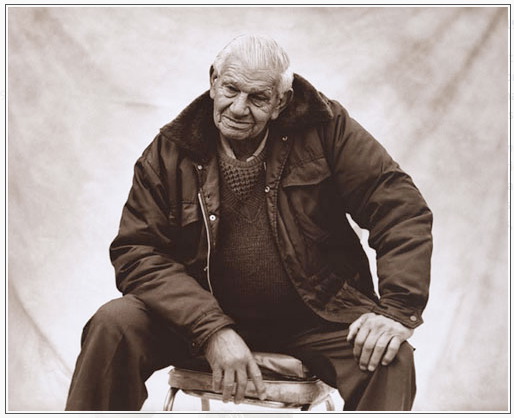

Sadly Riley died young, aged only 44, but the legacy he leaves behind eloquently builds on the rich traditions of storytelling and symbolism of his ancestors. His work is powerful, challenging, political and impressively lyrical. The series of portraits of the residents of his mother’s and father’s home towns of Moree (A common place: Portraits of Moree Murries 1990) and Dubbo (Yarns from the Talbragar Reserve 1998) are a rare and intimate celebration of ordinary aboriginal people, at ease in the place they call home. For me the simple earthen toned background to the sitters is reminiscent of a sheet of stone, giving these insightful portraits an uncanny resemblance to ‘rock art’, but instead hewn from a contemporary medium. And in their simple and spare frames each subject ineluctably hinting at Riley’s aspiration for the immutability of his people, their culture, and their richly visual tradition of art, an art inextricably tied to the land, their land.

Willy Hill © Michael Riley 1998

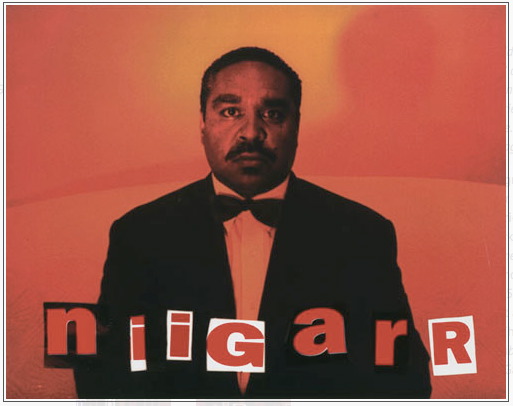

But Riley was not afraid to be overtly political and explore the experience of being a black man in ‘modern’ Australia, confronting head-on the racist taunts and jibes that he had experienced as a youth in his series ‘They call me niigarr’.

“They call me niigarr reflects on childhood school days when you used to get called names like ‘nigger’, ‘chocolate’ or ‘sambo’, ‘vegemite’. All these lovely racist names that not only the students but the teachers would call you. They call me niigarr was a portrait of a friend of mine – an Aboriginal person in a black Armani suit sitting on a lounge. He’s reflecting what those words are or were, juxtaposing the words and images together.” © Michael Riley

These are a powerful appropriation of the language of oppression – using the transmutative ability of art to signify strength: of character, culture and belonging.

Niigarr © Michael Riley 1995

I suspect Riley would have been more dismayed by the comments from the National Gallery of Australia than he would have been by being called a “niigarr”. At least the latter, however distasteful and pejorative, acknowledges his physical presence.

For their part, rather than lament what they failed to obtain for their collection, the National Gallery might do better to give some consideration to the astonishing range of aboriginal rock art that is under constant threat of destruction from vandalism, erosion and industrial development and the loss of which will be far more damaging to Australian visual culture than the absence of the Stubb paintings. If this ancient artistic heritage is allowed to disappear, with it will go the rich and and symbolically powerful story of the first inhabitants of this vast continent.

The Stubb paintings, and the comments uttered over their loss, represent only the story of Australia’s very recent colonization.

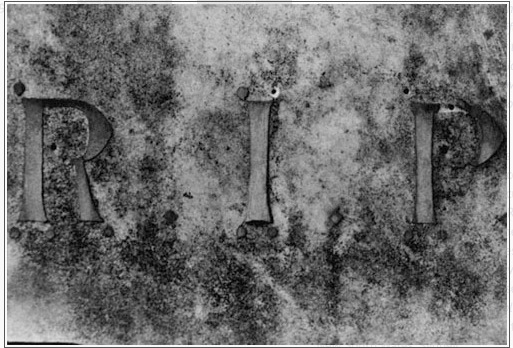

Untitled from the series ‘Sacrifice’ © Michael Riley 1992

I’ll let Michael Riley himself have the last word, from an introduction to his 1992 series ‘Sacrifice’ a starkly powerful body of b&w images that reflect on the continuing effects of substance misuse and religion, and their role in the colonization and oppression of aboriginal people.

As Aboriginal people, we have to sacrifice ourselves, something of ourselves, all the time to be a bit more like what non-Aboriginal people want us to be. Sacrifice was the first conceptual exhibition; the first time I had reflected on Christianity, and history of mission life, Aboriginal missions. I was exploring images from childhood – being sent to Sunday School and wondering what the hell this strange concept of religion is for an Aboriginal kid growing up in the bush. It’s about history, about how Aboriginal people were thrown onto reserves and missions and told not to speak languages, not to conduct ceremony or song. © Michael Riley

Discussion (9 Comments)

Once again, a great piece, John. You are a mine of knowledge! Actually though, this piece got me thinking about various things to do with race and conditioning by media and/or life experiences. For example, why when I think of Australia, do I ‘see’ it as a ‘white’ country before remembering the Aboriginal people (the same would apply for New Zealand and the Maori people), whereas, say, for Cuba or Brazil, I’m well aware of the various peoples and shades of skin colour? Thinking about it, in media terms, the Aboriginal people of Australia seem to be rarely shown/reported and when they are, they often seem to be shown in a sorry state – or perhaps that’s just my perception (of the media, not the Aborigines).

Thanks Tony. I thought the comment reported was outrageous. Aboriginal culture is astonishing. But your perception is correct – there’s long been a failure to promote aboriginal culture in as positive a way as it deserves. The history of the treatment of aboriginal people is shameful. There’s been numerous photographers who’ve turned their cameras on Australian aboriginal people, and of the non-natives I have to say English photographer Penny Tweedie’s work impressed me the most. She was very committed and had a conscience, and produced work that has endured. She was a great photographer all round, her obituary is remarkable. Her website is still maintained and is well worth a visit here.

Thanks for the PT link, John. Interesting stuff.

You’re welcome Tony. I remember being bowled over by her work when I was younger, I think in the Sunday Times, various essays over the years, some powerful work on aboriginals, about alcoholism and oppression, life on mission stations, the clash of cultures as elements of the new Australia tried to shake off what it seemed to perceive as the burden of its aboriginal heritage. But what struck me was the dignity she managed to portray. Never opportunist, always with that edge of concern and humanity that elevates the really really good photographers from all the rest.

Yes John, it’s a shame that the dignity of “the other” is sometimes undervalued or overlooked altogether. In today’s mad-cap world, I fear that could well get worse. The work of photographers like PT are a reminder not to let it be so.

I know what you mean. There’s a good post on Fototazo yesterday you’ll maybe enjoy: http://www.fototazo.com/2013/11/the-white-stuff.html

Thanks John. It raised some things I’ve been thinking about lately in my own photography.

This such an important subject. Thank you for raising it.

Thanks Erin. That not one single journalist challenged this statement is such a damning indictment of our attitude towards indigenous peoples. They are, to all intents and purposes, invisible. In any country it would be shameful, but in Australia with the phenomenal importance of the visual in aboriginal art, and its significance as a cornerstone of their culture, such an attitude is inexcusable.