“Do you see it? Understand it? Ok..” (“The mysterious perversion of photography”)

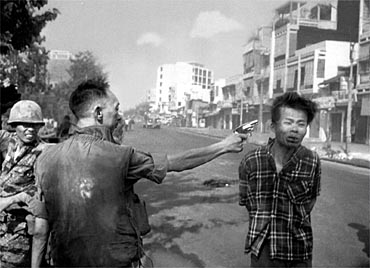

Written by John MacphersonThere’s an interesting article in the NYT Lens blog by Donald R. Winslow: ‘Eddie Adams: 10 Years On, and War Will Never Be the Same”

“When Eddie Adams died 10 years ago today, many people thought his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1968 picture, “Saigon Execution,” would be one of history’s most graphic, violent and enduring war photographs. It was hard to imagine its power — splashed across front pages and helping to turn public opinion against the war — ever being surpassed. Horst Faas of The Associated Press called it the “most perfect news photo I have seen in my 50 years of photo editing.”

But little did we know what was to come in the decade after Adams’s death.

When Adams was one of the world’s top photographers, professional photojournalists were guided by editors and backed by their newspapers, wire services and agencies. Today the perpetrators and combatants — from Mexican drug cartels to the ISIS rebels who behead their captives — have become a growing source of images, shooting, editing and releasing their own photos and videos. As they attempt to control the message, honest and ethical journalism risks being shoved aside in favor of images that are pure propaganda, if not outright fabrications.”

Image © The Associated Press. (AP Photo/Eddie Adams)

Donald Winslow goes on to lament what he sees as the loss of power of the images of today:

“But on this 10th anniversary of Adams’s death, I’m wondering if he would still say that photographs are the most powerful weapon in the world. These images no longer connect me with the dead. They just don’t have the power they had in 1968. They don’t seem to move public opinion, government or the world as they once did. Are we desensitized by the sheer volume of violence? Have we as viewers become empathetically bankrupt?”

I disagree to some extent with the notion that images are losing their power. Quite the contrary. I suspect what we are witnessing is ‘simply’ * a change in the way that their power is being harnessed and used. (* except its not really that simple). And also the ease (as is pointed out in the Lens article) with which images may be misappropriated, or even created as deliberate propaganda tools – I would suggest there is no imperative to do that unless there IS still a belief in their power. That ISIL and others are adopting this strategy simply underlines THEIR belief in the power of the image to deliver a message, something we would do well to heed, however disgusting we find it.

Indeed I would contend that it was not just fear of offending people that prevented Jarecke’s Iraqi soldier from being published, but fear of it’s power. For the full story behind Jarecke’s image the recent piece in The Atlantic ‘The War Photo No One Would Publish’ by Torie Rose DeGhett is well worth reading.

But, in some respects, things have changed since Jarecke’s image was made, no longer is it solely a top-down delivery of ‘news’, with newspaper editors the arbiters of what is seen or not, rather it is a more democratic process of people appropriating, curating and sharing through social media, if not actually creating the representative images themselves (as done in Ferguson MO).

Local community residents guard store. Ferguson MO

In fact if it were NOT for the images coming out of Ferguson from local (predominantly black) people the overwhelming narrative of that event would be hugely biased and condemnatory of the resident black community. But having said that – within only 24 hours of positive images of Ferguson residents being posted online by the community, they were themselves misappropriated by right wing white commentators and re-used out-of-context in a very pejorative way http://www.duckrabbit.info/2014/08/these-black-men-represent-a-threat/ But again I would suggest, amply demonstrating an unshakeable belief in the power of the image to deliver a (damaging) message.

But, that easy access to image creation and sharing has brought with it a problem – one that governments and police wrestle with daily – which is that images enable a degree of scrutiny (of their activities) that is hard to refute thanks to the ubiquity of imaging equipment in the hands of the wider public, and combined with the immediacy of sharing. http://www.duckrabbit.info/2014/08/the-thin-blue-line/

Where any true lack of power lies in my opinion is perhaps at a political level. Few ordinary people I know who were even remotely aware of recent events in Gaza failed to be horrified and profoundly angry, but our elected representatives chose the ‘diplomatic’ option (basically wring hands and tut-tut, but continue with business as usual). If there is a perceived loss of democratic power to effect change it is perhaps towards government we need to turn, and more robustly question why.

A compelling reason why I think some of what we accept as ‘war photography’ needs to shift its gaze slightly, towards the purveyors of terror rather than to continually focus (often simplistically) on the damage that their policies cause. And that is not to ignore some of the powerfully compelling and important work done in this vein such as Hetherington’s ‘Sleeping Soldiers’, and Ash Gilbertson’s elegiac ‘Bedrooms of The Fallen’. We need more work like this which explores the high price we pay for conflict. Work that asks different questions, discomforting questions (of politicians), ones that demand answers that are much harder to find.

Whilst individual images still can wield power I see more and more often the power of curation and forensic use of photographs, and whilst not specifically a ‘war’ image a good example of the forensic use of imagery is Pete Brook’s analysis of the death & photographing of Fabienne Cherisma in Haiti, a powerful piece of investigation of the ways photographs are taken and used, and what that may say (about all of us) http://prisonphotography.org/2010/01/27/fabienne-cherisma/

Fabienne Cherisma © Carlos Garcia Rawlins/Reuters

“Fifteen year-old Fabienne Cherisma was shot dead by police at approximately 4pm, January 19th, 2010.

On the 26th of January, the Guardian published an account of Fabienne’s life – her schooling, her sales acumen and her aspirations to be a nurse. The piece is not long, but it needn’t be. It is a modest effort – hopefully the first of a few – to remind us that Fabienne was a daughter, a sister, a source of love and pride for her family and, in the end, an innocent victim.

THE IMAGE THAT REMAINS, THE SYMBOL THAT EMERGES

There is a chance that Fabienne Cherisma could become a symbol of the Haitian earthquake and the problematic aftermath; that she become a tragic silhouette extending meaning far beyond the facts of her abrupt and unjust death.

This notion can be at once offensive and inevitable. If the visual rhetoric is going to play out as such, then if it is not Fabienne, it will be another victim.

What purpose could the emergence of a such a symbol serve?

If one believes that images fuel public awareness, thus securing donations and aid, and thus helping Haiti’s immediate future, then certain images and stories will carry that awareness and emotion.

All the accusations of media exploitation in Haiti do not discredit the positive effects a single image can – without any manipulation – have in the minds of millions. I wouldn’t call this the magic or the power of photography, I’d call it the mysterious perversion of photography. I don’t, and can’t, explain it. I merely observe it.”

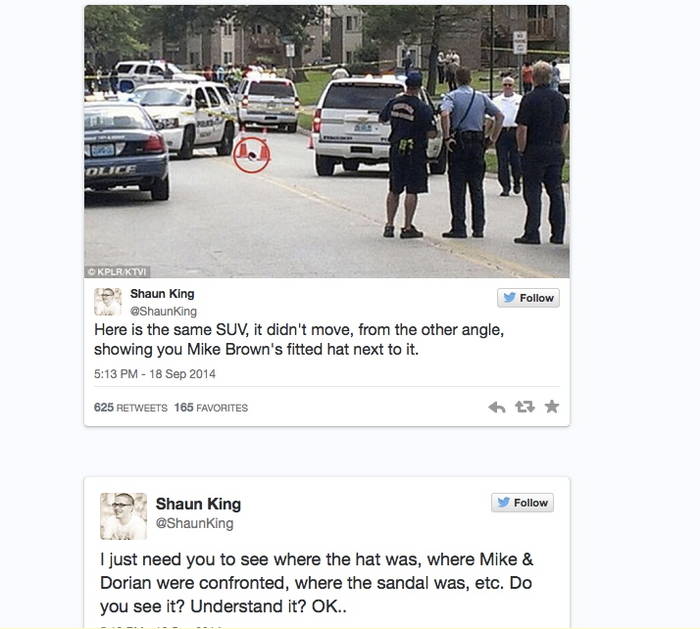

And also more recently, for example, there is the examination by Shaun King of the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, using widely available photographs for reference and analysis purposes, here: https://storify.com/VeryWhiteGuy/shaunking-exposes-ferguson-pd-lie-about… (which in an internal link also reveals the extent of the reluctance of Police unions to adopt body-worn cameras: http://www.kmov.com/news/local/Tensions-between-St-Louis-Police-officers… ) again, perhaps a good indicator of authority’s fear of the power of images to hold them to account.

All of which demonstrates that not only were the photographs taken by ordinary people hugely important in Ferguson, in real time, but they are proving useful afterwards to tackle head-on the possibility of Police corruption and collusion. That’s pretty powerful stuff being done by and with images.

But there is another side to that coin – the recent case of misappropriation of one of Ami Vitale’s images, used out of its original context to illustrate a campaign to free the kidnapped Nigerian schoolgirls, which attracted a lot of attention (link). But as I discovered, using the same tools that enables photographs to go viral, was that the misappropriation and misuse of that image in very pejorative ways was massive, literally hundreds of uses, perhaps diminishing the integrity of it (and definitely diminishing the humanity of its subject), but certainly uses that are wholly reliant on that one image’s perceived power to affect and engage people.

Image © Ami Vitale

Noam Galai’s ‘The Stolen Scream’ is another good example of an image becoming powerful and iconic simply by being shared and widely adopted. http://screameverywhere.com/ One unlikely image, not even of ‘conflict’, but unexpectedly, and powerfully misappropriated to become the visual slogan of many oppressed people.

So I guess what I’m saying in a long-winded way is that images still have power, and we need good photojournalists to produce some of them, but that the democratization of image-making and sharing has allowed many other ordinary people to participate in that process too.

But sometimes the power can be, and often is, imbued in those images by curation, or simply sharing. That latter point being the crucial one – ISIS rely on our willingness to collude in distributing their images, because they know absolute censorship is our alternative, and understand that such restrictions are virtually impossible today, and any attempt to do so would be contentious and damaging.

But here’s where it gets difficult. There’s one thing missing from Winslow’s lament. This paragraph provides a clue:

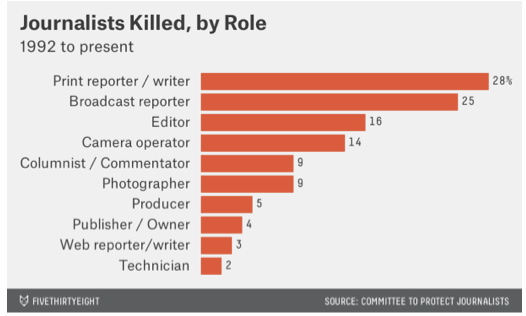

“But today’s generation of photojournalists can no longer cover many conflicts because the risks are too great. It’s suicide. Newspapers have stopped sending staff members, and freelancers — like James Foley or Steven Sotloff — are filling the void and paying the price. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, more than 80 journalists have been kidnapped and 71 killed since the war in Syria began.”

The depressing fact is that no longer is it sufficient to unearth compelling stories, take insightful nuanced images, and tease out the overlooked details of conflict, as was done by Hetherington, Hussain, Niedringhaus, Barakat, al-Shami, Martin, Ochilik and many others who gave their lives covering conflicts on our behalf.

The harsh fact is the work of some of these (western) (photo)journalists was relatively overlooked by the wider media. It took their untimely deaths to catapult their work into the forefront of media consciousness. Suddenly their true abilities were given public recognition, and quite rightly lauded. Each one finally, in death, given the praise they deserved for the work they’d struggled to produce and have seen whilst alive. But what kind of state is the modern media industry in that it takes the death of the messenger to enable the message to be seen, heard, and maybe even listened to?

And more importantly what message does this send to organizations like ISIL, bent on maximizing their media ‘reach’ in any way they can: that a guarantee of media exposure is to shoot (behead) the messenger?

To conclude, I think I agree with Fred Ritchin, that we need to take the long view, that these images still need to be taken however we may manage that – and this is all about proper training, equipment and education for young and aspiring journalists especially those foreign nationals doing dangerous work locally on our behalf – and not lose sight of the fact that these images may have their moment in the future, their latent power finally utilized to hold to account those whose actions deserve the harsh glare of justice, and the unrelenting gaze of history.

Maybe we just need to accept this as an evolutionary process, work through the disruptive influence of digital imaging and sharing, be dismayed by what it prevents and what we lose as a consequence of it…………but grasp all that it enables, and try to do this as best we can with an eye to the future, and the one thing we possess that can inform it: integrity.

And to answer (perhaps) Winslow’s own observation, and I hope, maybe to rouse him even just a little from the genuine dismay he imparts:

“These images no longer connect me with the dead. They just don’t have the power they had in 1968. They don’t seem to move public opinion, government or the world as they once did. Are we desensitized by the sheer volume of violence? Have we as viewers become empathetically bankrupt?”

Maybe they do no longer “connect (us) with the dead”, but what they can do, and do incredibly well through social media…….as demonstrated by the misappropriation and compelling use of the work of Vitale and Galai and others……….is connect us with the living. And therein lies something infinitely precious and powerful we have yet to fully realize the potential of.

And there, perhaps, is where Brook’s “mysterious perversion of photography” may lead us.