Fact, Fiction & Manipulation

Written by John MacphersonI came across two thought-provoking image series one day last week. Each one was technically superb, the result of painstaking work by talented and committed photographers. Both dealt with difficult and contentious issues, of (sexual) exploitation, rural isolation and social marginalization. Both were ‘documentary’ projects, made by photojournalists. However one was ‘fact’ but presented as ‘fiction’, the other ‘fiction’ but presented as ‘fact’.

Suzanne Smoke, Alderville First Nation

Paired with birds sitting on a telephone wire near Alderville First Nation in Ontario. © Daniella Zalcman

Sound a bit confusing? I’ll try to explain:

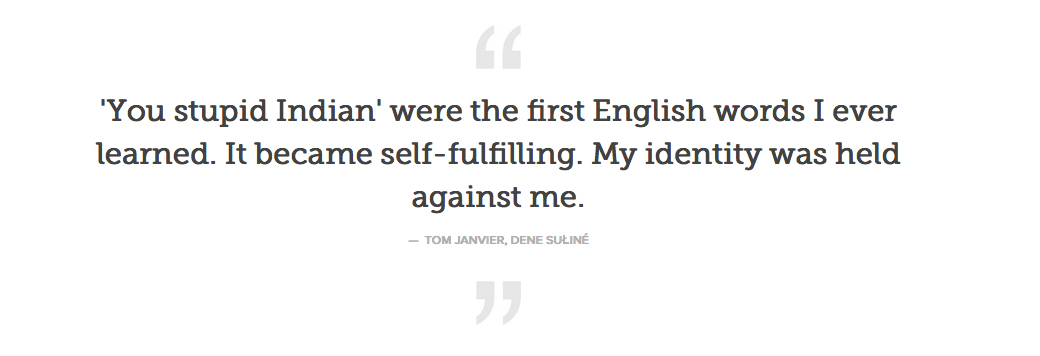

Daniella Zalcman, in Mashable, presents obviously ‘manipulated’ images of members of Canada’s indigenous populations in her project ‘Lost Generations‘. These are striking double-exposures, in muted tones, that explore the experience and consequences of forcible assimilation into Canadian culture that affected many indigenous children.

“In the 1840s, the Canadian government established the Indian Residential School system, a network of church-run boarding schools created to forcibly assimilate indigenous children into the dominant culture of Canada.

The children who attended these facilities — coming from First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities — were punished for speaking their native languages or observing indigenous traditions. They were routinely physically and sexually abused, both by the teachers who ran the schools and by older students who had typically been assaulted themselves. In some extreme instances, students were subjected to medical experimentation and sterilization by teachers and school administrators.

The last residential school didn’t close until 1996. The Canadian government issued its first formal apology in 2008.”

Zalcman describes her underlying idea:

I paired individuals with sites where residential schools once stood, government documents that enforced strategic assimilation and places where First Nations peoples now struggle to persevere. Each double exposure contains an echo of trauma, which lingers even during the healing process, as languages and traditions return.

The result is a series of intriguing multi-layered images that tease and provoke the viewer.

Multiple exposure images are interesting. You may record one layer with deliberate intent and accuracy, and then a second layer, again with great precision, but the ‘third layer’ – that amalgam of both – is where the alchemy occurs, and where the power resides.

In contemplating these complex visual creations, and through their multi-layered metaphors, the viewer is forced to confront the shape-shifting reality of the subject’s lives. These are lives rooted in trauma, yet in these images those pictured confront that knowledge head-on, bound irrevocably to it by reference to place or text, but in that ‘third layer’ of ‘fiction’ living and growing beyond the narrow confines of that experience. The result is cathartic for the subject, and I personally find them to be profoundly moving, and inspiring.

The other set of images, in Featureshoot, is by photographer Txema Salvans in the project ‘The Waiting Game’, who

“……….captures a unique view of prostitution happening in urban and rural roadside locations along Spain’s Meditarranean coast in The Waiting Game……….

………Knowing that these women would likely not want their photos taken for obvious reasons, Salvans cleverly disguised himself as a surveyor, accompanied by an assistant carrying a surveyor’s pole. He managed to get some fascinating shots, ones that present these women in a much larger context. We see quiet moments of waiting, unaware of what these women may have just experienced or of what’s to come.” (quote from article by Amanda Gorence)

Salvans’ images are quite beautiful, the Mediterranean light is allowed to dominate and the sense of heat and space is beautifully wrought. My disquiet however comes from the ‘fiction’ they present.

The question they raise for me is: are these really prostitutes?

The photographer doesn’t know for sure, he never asked them, so all he’s doing is guessing. I could produce the same images and say these women are “…ikea chair testers…” or “…women waiting for taxi to go to a party…” or “…researchers looking at Post-Industrial Society Structural Change and Service Sector Employment in Spain…“ and dare you to contradict me. The problem is that IF these women were actually doing any of the things I mentioned, to call them “prostitutes” could have consequences for them that did not exist before that label was arbitrarily applied to them.

Cameras work both ways. They reveal two sides. We have no idea who the women in front of the camera are, nor what they are doing. But we certainly know what the man was doing.

Where is the fiction? I think it is everywhere in this work. In fact its foundation is a fiction too:

…..the women ‘saw’ a man dressed up and assumed he was a surveyor, but he was actually a ‘photographer’.

…..the photographer ‘saw’ a woman dressed up and assumed she was a prostitute, but she could have been anything.

Without the voice of the subject, the only ‘truth’ this represents is the photographer’s, and his is a somewhat disingenuous voice.

The wider, and potentially troubling implication of this work, is that women anywhere, dressed similarly and in a quiet roadside location, can be legitimate subjects for speculation and assumption about their profession and social status; and there may follow undesirable consequences. That makes me distinctly uncomfortable.

Simply presenting the work as a thematic series and leaving the ‘assumptions’ about the subject’s presence and profession to the viewer would have been far more appropriate. In doing so it would more accurately reflect the reality of the situation, ‘turning the tables’ in a sense, raising questions about the viewer’s experience and knowledge, and allowing THEIR interpretation to create the ‘reality’ that these images may represent. And that ‘reality’ may only be a ‘fiction’ in their mind. Without the labels already guessed at and applied by the author, the women can be whatever the viewer wants them to be.

And it’s worth remembering that when not in these locations, and defined simply by geography, these women are I would ‘guess’, something else: friend, mother, daughter, sister, lover, cook, driver, cleaner, lawyer, physicist.

Labeling them, as the photographer has done, has I feel reduced the impact of this work. Labeling anyone, in the absence of their own voice and description of self, can be potentially damaging.

Daniella Zalcman hits the ethical nail bang on the head when she says:

But one of the many problems with images depicting drug use, alcoholism and poverty is that they can do more to shame and stigmatize the subjects than shed light on the sources of their suffering. In an attempt to overcome that challenge, I created multiple-exposure portraits to look at the causes, rather than the effects.

These are two powerful and visually impressive bodies of work, but the way in which each ‘story’ is presented in a ‘journalistic’ sense is profoundly different.

Curiously given the rules* of, for example, the World Press Photo competition, Zalcman’s images would I presume be ineligible for entry due to their ‘manipulation’, but Salvans images would be perfectly acceptable **. Given that the WPP aims to promote and celebrate “visual storytelling” maybe I’m not the only one who finds this rather surprising?

For 60 years already, World Press Photo has encouraged the highest standards in photojournalism. The resulting archive is not only a record of more than half a century of human history, but a showcase of successive styles in visual storytelling.

(quote from the WPP website)

Which begs the question: what is more ‘honest’ – to manipulate your images to present a visual fiction but one that is constructed from layers rooted firmly in ‘fact’, or leave your images untouched but manipulate the mind of your viewers and their consideration of the subject, by means of captions woven from assumption?

‘The camera never lies’, so the old saying goes, and I guess it’s true, we are more likely to be ‘misled’ by the hands that hold it.

* See here, WPP Competition 2014, Rule 15: “The content of the image must not be altered….” and Rule 16: “Only single-frame images will be accepted.”

** Update: Daniella Zalcman has confirmed that she has sought clarification of her work’s eligibility for WPP and has been told it is not eligible due to manipulation (double exposures).

Discussion (9 Comments)

This is a superb post John. So much food for thought.

Thanks ducks. I really love the aesthetic of Salvans’ work but the underlying theme really perplexes me. It was unnecessary to ‘make it up’ and fact is the work would stand perfectly well without the caption guesswork.

That it can still be a WPP worthy portfolio is bizarre when contrasted with Zalcman’s work which deliberately breaks the visual convention required for WPP, and therefore excludes her.

The latter work though speaks more honestly and directly about the subject, and confronts the problems of representation/stigma in ‘photojournalism’ head on, and finds a solution, a clever, thought-provoking and humane solution at that.

If WPP wants to promote ‘visual storytelling’ that has at its heart integrity. and crucially – is subject-led – then they should find a way to reward Daniella Zalcman and set an example that others can follow. This whole tail-chase over ‘manipulation’ of images is a red herring. Manipulation is something that can happen totally independent of the image, as the Salvans work demonstrates.

But I still like his work very much!

It’s particularly appropriate to question a photographer’s motivation and MO

when undertaking any project that involves the stealthy recording of individuals (even when in public). And I too had some reservations about Mr. Salvans work at first, but came to peace with it after some (what I thought measured) consideration. I was particularly wary since there was a photojournalist who in the recent past went around photographing inner city residents from the confines of a car with a concealed camera. Offhand, the MO of both projects seemed disturbingly similar…

First off, I think that it’s a bit disingenuous and naive to assert that these women are not prostitutes. They are located in very isolated areas for hours at a time, are not waiting for the bus, are not hitchhikers, and are most certainly not Ikea chair models. I think it would be an insult to independent sex workers, and worse, to those forcefully coerced into the business to make believe otherwise.

Unlike, the urban situation where they could have asked someone to either

invest the time or assign someone who had more credibility with the residents- I don’t think Salvans had that opportunity. These women work very much in isolation, they aren’t accessible as a “community.” Most of them probably have to deal with pimps, sex traffickers- you name it. So not only was it a case of how to catch candid photos of real life in real time, it was also a case of not endangering all concerned- photographer and subject alike. I think in this case, Mr. Silvans solution was not only ingenious, but also the most ethical under the circumstances- although I would also hope that his work does not exist solely for its own artistic value and consumption, but would also serve to actively lead to a closer examination of the global nightmare called human trafficking.

That said, I do have the book (at home) and will reread to see if any of the questions raised here are more fully addressed or answered. I do agree that we are, in fact, at a very real loss without input from the subjects themselves…

Forgot about this interview where Salvans talks about the situation many of these women find themselves in. And, of course, this kind of “trade” (prostitution is legal in Spain- as for human trafficking…) could not exist in the open without a certain amount of corruption on multiple levels.

Are the photographs exploitative? One could say that the majority of johns at least pay for their services, or… that they are no more exploited than anyone else who gets photographed by a pj without compensation. Either way, despite the great images that these photographs most definitely are, one cannot walk away without a bad feeling in your gut for the majority of these women. Also makes one wonder how Mary Ellen Mark would have approached the situation, or if she could have.

http://www.thegreatleapsideways.com/?ha_exhibit=the-waiting-game-an-interview-with-txema-salvans

Hello Stan thanks for commenting. You make fair points, but to be honest ones I did consider before writing. It’s “disingenuous and naive” of me – well of course it is, and deliberately so, simply trying to crudely point out that labels are easily applied and in the absence of the subject’s own voice and frame of self-reference anything is valid.

It may be the case that if asked these women would describe themselves as prostitutes, but one thing is key here, as it was in Henner’s Streetview work – that the artists’s assumption about these women’s ‘trade’ is defined simply by geography, and not by the subjects themselves. I’m more interested in the contrast with Zalcman’s images – dealing as they do with contentious and stigmatising events – and the way she has used a ‘factual’ presentation but created a fictional narrative that manages to circumvent (at least in my mind) some of the issues of pejorative labeling that can adversely affect subjects.

I’m perplexed by the fact that the former’s work, based on a simple assumption assigned the work by dress and place, is valid for WPP and yet the more ‘truthful’ work of the latter is not.

Salvans wore a disguise to create the work, and if only one of the subjects was a bold academic similarly disguised pretending to be a prostitute for research purposes then the whole facade of the piece falls apart. We just don’t know for sure and to assume otherwise is problematic.

One thing that puzzles me though – and its a hugely important point – given the years that Salvans spent doing this he must have witnessed a driver stop and pick up one or more of the women – why none of that portrayed? Even a multi-layered presentation as Zalcman has produced, with details obscured? It just seems its easier to portray one side of the issue than the full picture. And again thats a ‘power’ thing – women are easier subjects than the pimps and johns who interact with them.

And indeed that then begs the question – did the presence of the ‘surveyor and assistant with pole’ actually prevent drivers from stopping, fearful of identification, and Salvans presence therefore had an economic impact on the women, and ironically caused there to be no evidence of ‘prostitution’ that the photographer personally witnessed – the presence of the observer affecting the outcome.

Bottom line I have no problems with the work, I love the aesthetic and the idea and I guess also the execution too, it’s important work. What I have a problem with is the labeling – it was unnecessary, the inference of what these women are doing should have been left to the viewer. It would have teased out from the observer’s their own prejudices and understanding of what women do in these places, in these clothes.

Sometimes letting the viewer bring something personal to the ‘contract of engagement’ with a body of work is of far more worth in underpinning the validity of it.

Appreciate your engagement, thanks very much.

Not to be argumentative, perhaps we’re just arguing matters of degrees. I think the subject (ie- problem) of labeling is a valid one- particularly as someone who has experienced being a: “minority student,” “minority teacher,” “minority photographer” and just plain “minority.”

I’d have a problem labeling young men hanging out on a generic street corner as “drug dealers” if I was just passing through- I wouldn’t have such reservations if I knew it to be a known drug location and/or had previously witnessed said men dealing. I don’t think the fact that there may well be a cop working undercover there negates that reality. And that also doesn’t divorce my understanding of the complex social pressures that have placed those men there (true, that is not always the case with others, as may well be the case here) doing what they do.

So I am not that disturbed by having these women (dressed as they are AND specifically located where they are) labeled as prostitutes. Again, if I saw peasants toiling in the field in Romania, they may well be CIA operatives, but…

Salvans undoubtedly saw many a transaction during his project, and his is undoubtedly what seems a very superficial view of such highly problematic subject matter. Ironically, The Waiting Game, sticks to its title, and in so doing, presents us with a side of this business that is very seldom witnessed or acknowledged. They are very beautiful photographs of very unfortunate, even horrid circumstances- not unlike much of Salgado’s work.

PS- The very last shot in the book does show a car stopped with a “prostitute” leaning into the vehicle.

PPS- Didn’t comment on Daniella Zalcman’s work since, good as it is, I am not that familiar with it.

I don’t think we’re arguing here, and I see more agreement between us than disagreement.

I think my bottom line would be – leave the assumption and inferences to the viewer rather than overtly label.

I’m a firm believer in giving your audience both credit for being perceptive, and the opportunity to bring something of themselves to the transaction. Both their prejudices and affinities.

The very strength of this work – that is – who are these women, what circumstances have brought them here, where have they come from and where are they going – has been subsumed to some degree by the act of trying to pin them down precisely as ‘prostitutes’ which constitutes only a small (but signficant) proportion of their experience.

“They are very beautiful photographs of very unfortunate, even horrid circumstances” – I could not agree more. And their (considerable) impact comes from that dissonance.

Very good points. Inaccurate captions are indeed manipulations. When WPP and other organizations ignore that, they’re just hurting the industry as much as image manipulation.

Another classic example of inaccurate caption: woman holding a baby/child is assumed to be ‘a mother’ in the caption, even though it could be a sister, aunt, relative, carer, neighbor, etc.

Thanks for reading and commenting Rodrigo. You’re right, we often make assumptions about subjects, based on gender, roles, and a host of other factors, and that becomes ‘fact’ by being written in captions.

Images may take on a life of their own and their subjects becoming anything the user wants them to become. The Ami Vitale case is a good example: http://www.duckrabbit.info/2014/05/tears-for-fears/